How Hardware Gets Hacked (Part 1)

2025-12-17 | By Nathan Jones

Introduction

Security is an important topic these days; one would hope, for instance, that the WiFi router in your home or the servers owned by “Big Bank, Inc.” are protected against malicious attacks from remote sources. But just as important as network security is hardware security: the protections that are put in place against attackers who have physical access to a device. In a previous article, I laid out what an attacker could do to compromise a device they were holding in their hands. In this and future articles, I’d like to make those techniques a little more concrete by actually conducting the attack and defense of a real-life embedded system. If you’re curious to know what it actually means to conduct a side-channel or a fault injection attack, or to defend against one, then read on!

A secure car and key fob

The secure system we will aim to build is that of a key fob for a car. Nominally, the key fob comes from the manufacturer and is keyed for your vehicle. Your key fob shouldn’t unlock any other car, and no other key fob should be able to unlock yours. Further, your car shouldn’t unlock for any reason other than your key fob sending it an “unlock” command.

This is an example of a system that, despite not being internet-connected, absolutely needs security protections! We don’t want a person to easily break into our cars, right?? (Believe it or not, though, this wasn’t always a design concern, at least not a major one. The earliest key fobs were equipped with codes so a car could authenticate them, but they were only static codes, meaning they never changed. Those key fobs were susceptible to replay attacks in which a person nearby could simply record the radio transmission from the key fob as it issued its static code and then play back that same transmission later to unlock the car.)

But unlocking and starting our car is only one function of our key fob. In our system, we want our key fob to do a few other things as well.

If we purchase a second or third key fob, we should be able to use our current, paired key fob (and a user-specific PIN) to pair that new, unpaired key fob. Attackers shouldn’t be able to make a paired key fob without both a currently paired key fob and the user’s PIN.

Figure 2: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Figure 2: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Also, we should be able to purchase and install additional features (such as remote start) to our key fob. Attackers should not be able to install features that didn’t come from the manufacturer, and a feature that’s been enabled for one car shouldn’t allow an attacker to enable that feature on their own cars, though.

Challenge question!

Can you think of any additional features that a real, production-level system should or could have? (A few ideas are at the end of the article.)

It’s no coincidence that this system exactly matches the challenge set forth by MITRE in 2023 during their annual “Embedded Capture-the-Flag (eCTF)” competition! That challenge was my introduction to hardware security, and I wanted to revisit it in this article series to fully explore how teams could have attacked and secured their own systems in that competition.

In the rest of this article, we’ll discuss what the competition is and how the baseline (i.e., insecure) system that was provided to each team was designed. In all future articles, we iteratively attack our own system and then implement security measures to defend against those attacks.

The MITRE Embedded Capture-the-Flag (eCTF) competition

MITRE is a not-for-profit organization established to “advance national security in new ways and serve the public interest as an independent adviser.” Their federally-funded research and development centers (FFRDCs) conduct research in fields such as aviation and transportation, health and human services, and cybersecurity, with the aim of “[enabling] the government and the private sector to make better decisions” (from the 2023 eCTF competition kick-off slides).

Beginning in 2016, MITRE began facilitating a capture-the-flag (CTF) competition using real hardware; an “embedded CTF”. The goal was (and is) to expose students to the importance of embedded security, to teach them the fundamentals of designing secure embedded devices (especially when 'physical/proximal access attacks' are in-play), and to connect them with jobs in the field.

The competition occurs in two phases: “Design” and “Attack”.

Figure 3: Source: https://ectf.mitre.org/

Figure 3: Source: https://ectf.mitre.org/

In the “Design” phase, teams do their best to secure an example system. In 2023 (the year I was introduced to the eCTF), the challenge was to create a secure car and key fob system, exactly like the one described in the previous section. Development boards from Texas Instruments were used to act as both “key fobs” and “car” and UART was used to simulate device communications, such as radio transmissions.

Figure 4: Unlocking and starting a car with a paired key fob. One TM4C development board is flashed with the "key fob" firmware and paired with the “car” (a second TM4C development board flashed with the "car" firmware). An unlock message from the "key fob" is transmitted to the "car" over UART. If the "car" chooses to unlock, it sends the list of features that have been enabled on the key fob to a computer over UART.

Figure 4: Unlocking and starting a car with a paired key fob. One TM4C development board is flashed with the "key fob" firmware and paired with the “car” (a second TM4C development board flashed with the "car" firmware). An unlock message from the "key fob" is transmitted to the "car" over UART. If the "car" chooses to unlock, it sends the list of features that have been enabled on the key fob to a computer over UART.

These systems have to provide a specific set of features while adhering to a number of security requirements. For instance, in 2023, a car was required to unlock itself if it received an “unlock” message from a key fob to which it was paired.

The car was not to unlock itself if it received an “unlock” message from a key fob to which it had not been paired (or for any other reason, I guess; this was “Security requirement #1”).

In the “Attack” phase of the competition, teams load their competitors’ code onto their own development boards. Flags are captured when a team is able to force a competitor’s device to violate a security requirement. For instance, in 2023, a team could have secured a flag if they were able to get an opponent’s car to unlock without needing a paired key fob.

The fact that an attacker has physical access to both the car and key fob not only simulates real life but also means that teams need to defend against physical attacks such as man-in-the-middle, replay, fault injection, and side channel attacks.

Challenge question!

How might you begin designing this system? Can you draw a block diagram or sequence diagram to show how this system could implement the features described (unlocking/starting, pairing a new fob, enabling new fob features)? (For now, don’t feel like you need to add any security mechanisms; more important to begin with is a simple design for a working system.)

Full details of the 2023 competition (including rules and technical specifications) can be found here. MITRE also always provides an insecure example each year for teams to start their projects with. The insecure example implements all of the required features for the given system, but does not implement any security mechanisms. Let’s walk through that 2023 insecure example now, to give ourselves an understanding of how that system operates.

The insecure example

As mentioned above, our system needs to do three main things:

- Unlock a car

- Pair a new fob

- (Package and) Enable a new feature

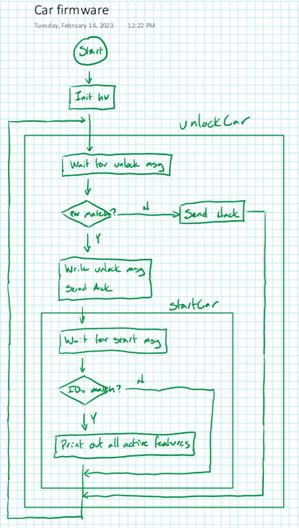

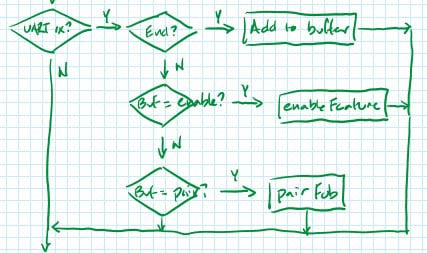

In the insecure example provided by MITRE, these functions were implemented in the key fob firmware (fob/src/firmware.c) and the car firmware (car/src/firmware.c). In the insecure example, both the car and the key fob run their tasks in an infinite loop. Inside each loop, the devices simply look for events that would trigger each feature, such as a button press to start the unlocking process or a UART message to enable a new feature on the key fob.

(NOTE: There’s a small typo in the fob firmware flowchart, coming out of the “End?” block, after “UART rx?”. The “Y” arrow [taken if an ending character (“\r”, “\n”, “\0”, or “0xD”) was received] should point down. The “N” arrow [taken if any other character was received] should point to the right.)

Let’s see how these two source files implement each of our desired features!

Challenge question!

Navigate to the source files mentioned above; are my flowcharts correct?

Follow along with my descriptions below; what subtleties are there in the code that we could turn into vulnerabilities?

“Unlock and start car”

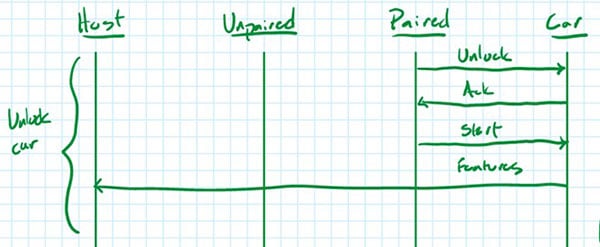

To unlock and start the “car”, an already-paired fob is connected to the car via UART. The car is also connected to a computer via UART.

Figure 5: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Figure 5: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

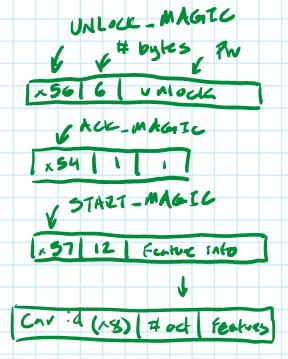

To implement this feature, the key fob looks for a button press in its main loop. Once detected, it sends out an “unlock” message over UART. If it receives an “ACK” message from the car, the key fob then sends out a “start” message.

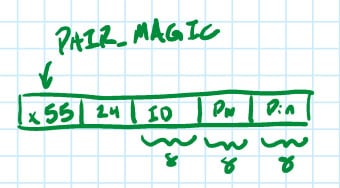

“Unlock”, “ACK”, and “start” messages use TLV (“tag-length-value”) format, meaning they all begin with a unique tag number (e.g., UNLOCK_MAGIC, which is 0x56, or START_MAGIC, which is 0x57), followed by a byte for the length and then the actual value/payload.

The payload of the “start” message contains the car ID (a unique 32-bit unsigned integer) followed by the number of active features (up to three for this competition), and the feature number/ID (1, 2, or 3) for each active feature.

The car firmware does one thing: continually look for the “unlock” message on its UART port. Once received, it compares the payload of the unlock message (in this case, literally “unlock” in ASCII) to an internal password value; if they match, the car transmits its unlock “message” (i.e., a flag) to the computer and sends the “ACK” message back to the key fob, then waits for the “start” message.

When the car receives the “start” message, it ensures that the car ID matches its own and, if it does, transmits a feature “message” (i.e., a flag) to the connected computer over a second UART port for each active feature number that was sent to it by the key fob.

We can summarize this interaction with the sequence diagram below.

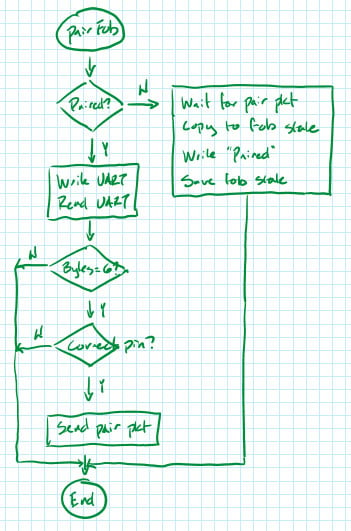

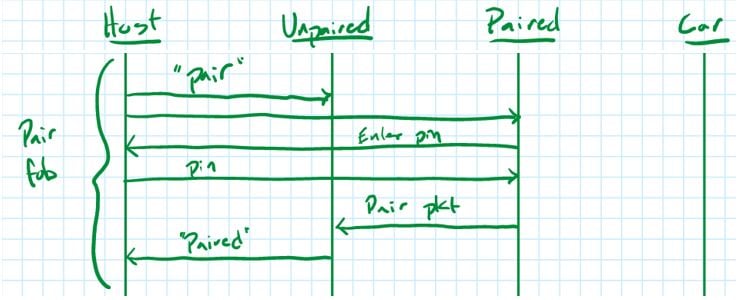

“Pair fob”

To pair a new fob, a paired and unpaired fob are connected to a computer, then to each other’s UART ports.

Figure 6: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Figure 6: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

To begin the pairing process, the host sends the word “pair” (literally the ASCII phrase “pair\n”) to both fobs. In each fob’s main loop, there is code that checks if this message appears over the UART.

When “pair\n” is received, the fob enters the pairFob() function. If the fob is paired, it sends back “P” and the host tool sends over the PIN entered by the user. If the PIN matches the one stored on the paired fob, then it sends a “pair” message to the unpaired fob.

If the fob is unpaired, it waits for this “pair” message. A “pair” message contains the car ID, password for unlocking, and the pairing PIN. With this information, the new fob can now successfully unlock the associated car and also pair additional fobs.

We can summarize this interaction with the sequence diagram below.

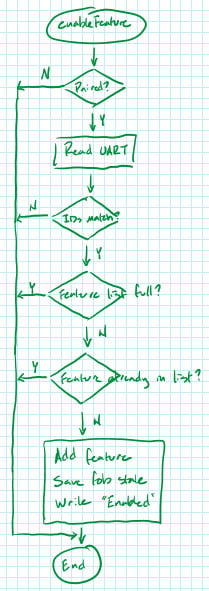

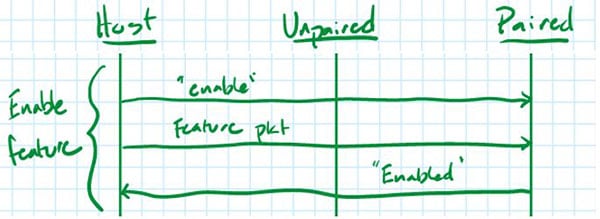

“Enable feature”

To enable a new feature, a single paired fob is connected to a computer via UART.

Figure 7: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Figure 7: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

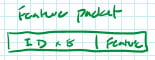

To begin the pairing process, the host sends the word “enable” (literally the ASCII phrase “enable\n”) to the fob, followed immediately by an “enable” packet, which contains the car ID (for which the feature has been enabled) and the feature number.

The information for the feature packet comes from a binary file created when the feature was packaged (see “Package feature”, below).

In the fob’s main loop, there is code that checks if this message appears over the UART.

When “enable\n” is received, the fob enters the enableFeature() function which checks to ensure that:

- the car IDs match,

- its feature list isn’t full (a maximum of three features can be enabled on a fob at any given time), and that

- the feature being enabled isn’t already enabled.

If all three items check out, then the fob adds the “feature” (literally an 8-bit integer) to its internal list of active features.

We can summarize this interaction with the sequence diagram below.

“Package feature”

In 2023, packaging a new feature was conducted by the MITRE staff, not by any attackers.

Figure 8: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Figure 8: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

The MITRE staff start the package feature process by running a tool on their computer, providing the car ID and feature number as command-line arguments. (This tool, among many others, can also read/modify a “host secrets” file to which attackers do not have access. The “host secrets” file can be used to do things like generate and track secret keys for cars, fobs, features, etc.)

Per the description above (in “Enable feature”), the binary file that’s generated would then contain just the car ID (padded to 8 bytes) and the feature number.

Attack phase operations

In real life, the designers of a system like this would build a threat model that described

- who they thought might target their system,

- what asset or feature they might be attacking, and

- how the attackers might target their system,

The designers would then implement countermeasures (i.e., defenses) to thwart those specific attacks.

In the MITRE eCTF, teams only need to worry about a small handful of security requirements. In 2023, the security requirements were as follows (from the rules, section 4):

- A car should only unlock and start when the user has an authentic fob that is paired with the car.

- Revoking an attacker’s physical access to a fob should also revoke their ability to unlock the associated car.

- Observing the communications between a fob and a car while unlocking should not allow an attacker to unlock the car in the future.

- Having an unpaired fob should not allow an attacker to unlock a car without a corresponding paired fob and pairing PIN.

- A car owner should not be able to add new features to a fob that did not get packaged by the manufacturer.

- Access to a feature packaged for one car should not allow an attacker to enable the same feature on another car.

As mentioned previously, attacking teams could capture flags by forcing their opponents’ designs to violate a security requirement. The set of resources the attackers were allowed to use in capturing those flags differed based on several different scenarios, called “cars”. In general, attacking teams always had access to opposing teams’ build tools and source code and to each car’s ID. Attacking teams never had access to opposing teams’ compiled binaries, which were encrypted by the competition organizers (except in the case of “Car 0”, but that car contained no flags), nor to any secrets generated by the build process (such as encryption keys, internal serial numbers, etc.).

Figure 9: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

Figure 9: https://ectf.mitre.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/2023-eCTF-Rules-v1.1-lr.pdf

For Car 0, attackers had access to the plaintext “car” and “fob” binaries (the only scenario in which they did) in addition to the paired fob’s pairing PIN and two pre-packaged features. Car 0 contained no flags, but was provided for the purposes of reconnaissance. It simulated an attacker buying a new car and then using any reverse-engineered information to break into other cars from the same manufacturer.

For Car 1, attackers had access to encrypted “car” and “unpaired fob” binaries as well as two pre-packaged features. Causing the car to unlock constituted a violation of Security Requirement (SR) #1, yielding a flag to the attacking team. This simulated being able to unlock another person’s car without their specific key fob.

For Car 2, attackers had access, at first, to the encrypted “car” and paired and unpaired “fob” binaries as well as two pre-packaged features. Attacking teams could then disable the “paired fob”, at which point causing the car to unlock constituted a violation of SR #2 and yielded a flag. This simulated being able to unlock a person’s car after having temporary access to their fob, such as one would have if they were a valet or could briefly steal a person’s car fob before returning it to their pocket or purse.

For Car 3, attackers had access to encrypted “car” and “unpaired fob” binaries as well as a logic analyzer capture of three unlock transactions between the car and its paired fob (and the two pre-packaged features, as usual). Causing the car to unlock constituted a violation of SR #3 and yielded a flag.

For Car 4, attackers had access to encrypted “car” and “unpaired fob” binaries as well as the pairing PIN for the paired fob (and the two pre-packaged features, as usual). Causing the car to unlock constituted a violation of SR #4 and yielded a flag.

For Car 5, attackers had access to encrypted “car” and paired and unpaired “fob” binaries as well as two pre-packaged features: Feature 1 for Car 5 and Feature 2 for Cars 0-4. There were two flags up for grabs in this scenario.

- Recovering the pairing PIN from Car 5’s paired fob constituted a violation of SR #4 and yielded a flag.

- Successfully enabling Feature 2 on Car 5 constituted a violation of either SR #5 or #6 and yielded a flag.

In subsequent articles, we’ll discuss how a person could achieve each of the flags described above, and then we’ll implement defenses against our own attack. Then we’ll attack our new code, then we’ll defend against that attack, then we’ll attack our newer code, then we’ll… Well, you get the picture.

Challenge question!

What are some ways you can think of to attack the insecure example? Brainstorm as big of a list as you can! For some ideas and for a peek at what we’ll do over the next few articles, check out “The Hardware Hacking Handbook” or the EMB3D website. Perhaps a few of your ideas will show up in the next few articles.

Sign up for the 2026 MITRE eCTF now!

Does this seem really cool?? Do you want to not just follow along but actually compete in a MITRE eCTF competition?? Then sign up before 31 January 2026 for this year’s competition! Heck, your local high school or college may have already participated at some point; check the “Past Competitors” list on the eCTF website to see.

The eCTF is open to “all US citizens and legal permanent residents 13 or older and most non-US citizens 18 or older” (see the participant agreement for all eligibility information and exceptions), with the sponsorship of a teacher or faculty member to act as a team advisor. Students at all academic levels are welcome to participate.

Additionally, MITRE is always interested in corporate sponsorship. If you work somewhere that might be interested in helping out with this great event, see here for more information.

Conclusion

Hardware security is important, and the MITRE eCTF provides an excellent and unique opportunity to practice those skills. In upcoming articles, we’ll dissect the 2023 insecure example, which implements a basic “car and key fob” system, by iteratively attacking it (per the competition rules) and then defending against those attacks. You can best prepare yourself to follow along with me by reading through the information on the 2023 competition page, specifically the rules and technical specifications, and by familiarizing yourself with the tools and insecure example provided by MITRE for that competition. In the next article, we’ll get the insecure example running on real hardware and then start attacking it! Are you ready to see how hardware gets hacked??

Solutions

Additional features

- The ability for a user to change or reset their PIN (if they’ve forgotten it or if they’ve sold the car)

- Batteries can be replaced without the device conducting a factory reset

- Over-the-air (OTA) updates for the fob or car firmware

- A way for the manufacturer to disable a feature (if it was based on a subscription model and the user has ceased paying for it)

- A way to make a “valet key”, with reduced or time-limited permissions for unlocking and starting the car

- A proximity sensor, so the car isn’t driven away without the key fob in it

- A “trunk open” button (keyed for your vehicle, just like the fob itself)

- An “emergency” button (keyed for your vehicle) with some ability to turn it back off

- A newly paired fob should subsequently have the ability to pair another fob to the same car